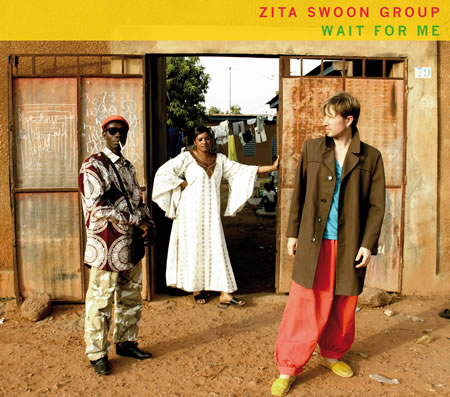

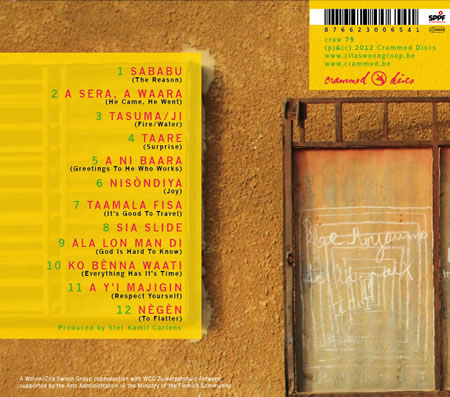

ZITA SWOON GROUP

Wait For Me

(Crammed Discs)

Wonderfully combining raw acoustic blues with traditional West African music, Wait For Me results from the encounter between Zita Swoon Group and Burkina Faso musicians Awa Démé & Mamadou Diabaté Kibié. Most songs deal with serious issues (often relating to the problems of modern African society), yet the album is uplifting and captivating: Awa's soaring vocals, Stef Kamil's raspy delivery, subtle instrumental textures, and inventive arrangements performed by eight excellent musicians all contribute to making Wait For Me a unique listening experience.

Having outgrown years ago the narrow 'rock band' framework, Stef Kamil Carlens is always eager to launch into new adventures. A couple of years ago, he travelled to Burkina Faso, and was introduced to singer Awa Démé and balafon (xylophone) player Mamadou Diabaté Kibié. Both are griots, popular traditional storytellers. This encounter turned out to be the starting point of a fascinating collaboration. Stef Kamil spent a lot of time with them, listening to their stories, and trying to get acquainted with their experiences and their way of seeing the world. Somewhat later, they started playing together, and soon found a way to combine Mamadou and Awa's West African melodies and patterns with Stef Kamil's blues-rooted style.

Most of the resulting songs are based around dialogues: the content of Awa Démé's lyrics (sung in Dioula, a Manding language) is echoed and transposed in Stef Kamil's English-language lines, which reflect the griots' preoccupations with traditional wisdom, interpersonal relationships, social codes and cultural traditions, but also with very current issues: social and political problems, the depletion of the country's natural resources, endemic poverty which drives many people to emigrate in search of a better life etc. Stef Kamil's lyrics sometimes expand on Awa's subject matter, and sometimes respond with a different viewpoint: in a song such as "A Ni Baara", Awa expresses the would-be emigrant's hopes, while Stef Kamil describes the hard reality which often expects the migrants.

Once the songs had been written, Stef Kamil Carlens moved to the next stage: creating a specific sonic environment in order to transform the core concept into a lively show and an interesting album. As with most recent Zita Swoon Group projects, Stef Kamil's starting point was to carefully select a series of instruments which would produce a palette of very defined tones and textures, whose combination would paint a certain picture and tell its own aural 'story'. The warm sound of the balafon is thus unexpectedly combined with the very idiosyncratic colours of the banjo, the resophonic guitar and the pump organ, augmented by an array of percussion, a bass guitar and a set of cocktail drums.

This very precise instrumentation was entrusted to a group of great players (some of which are regular Zita Swoon members, some not): young Cuban master Amel Serra Garcia plays percussion, Belgian/Congolese vocalist Kapinga Gysel plays pump organ and glockenspiel in addition to her backing vocal duties, Belgian guitarist Simon Pleysier mostly plays the banjo, the bass is entrusted with Christophe Albertijn (a composer and sound designer), and the cocktail drums with Karen Willems (who usually plays drums in an indie rock band). As for Stef Kamil Carlens, besides writing, singing and arranging the songs (both for the album and the live shows) with a meticulous attention to detail, he mostly plays resophonic and electric guitars.

After playing a first, acclaimed series of shows in Belgium in May, the band went into the studio to record the album, which was mixed by Gilles Martin (a longtime associate of Zita Swoon… and before that, of Crammed Discs, as he was practically the label's resident engineer/producer during the 2nd half of the '80s).

Such is the story of Wait For Me so far. What started as a solitary journey to West Africa has become an exciting, multidimensional affair: on the human level, a collective adventure involving people from two continents. On the lyrical level, an enlightening dialogue between two cultures, between two viewpoints on their respective realities. On the musical level, a new form of collaboration weaving African & "Northern" styles within an almost pop-like song format with seemingly effortless ease… as well as a fine piece of sonic art, with its delicate arrangements and bold choice of timbres.

Stef Kamil Carlens on Wait For Me

"Africa had always intrigued me, but until I took this trip – and except for a collection of CDs- it had always been a foreign continent to me.

Mamadou and I started playing, Mamadou on the balafon and me on the guitar. The limitations brought on by the balafon- the musical scale starts with fa- were an asset because you could immediately exclude a few things. After that it all went pretty fast, looking for a direction together, writing and our first recordings.

Mamadou and Awa live in the city [of Bobo-Dioulasso] but they remain villagers who can neither read nor write. Most of their songs come from the griot world, and they are founded in folklore or philosophy that is passed on from mother to daughter, or from father to son. The subject matter is diverse, mostly about people: about honesty, lying, betrayal... But sometimes it's about very specific current themes like ecology. The woodcutting in Burkina is massive to the extent that it is a threat to the eco system. There's a song that cries out to burn down less woods and cut down less trees.

Modernisation in Burkina Faso is slow. There's been a dictatorship for 23 years; there is the very dry sub-Saharan climate and cotton industry multinationals are killing small farmers. Mali and Burkina are the biggest cotton producers in Africa, but their production depends completely on manipulated crops, which don't produce their own seeds. Each year farmers are forced to buy these patented seeds from large multinationals and pay high prices for these. And we're not even talking about the monoculture and the amount of water it takes.

We talked for nights on end. People talk about liberalism, in the sense of opening up the community. People also think dictatorship has to go, and that women should have more rights, that education should improve. But at the same time, people wake up wondering what they're going to eat that evening. 'A hungry man is not a free man', I heard that sentence so often… I spent many evenings with my fantastic guide Ibrahim Diallo and listened to his compelling life story and the stories of others.

I find the importance of social codes in Burkina Faso fascinating, the social rules the Burkinese employ with 'les étrangers' for whom they'll drop everything. As a stranger in Burkina, you're treated like a prince, regardless of who you are or where you're from. I don't believe we've ever had such codes in our culture or genes. We can learn a thing or two from this."

[To maintain unity in the cultural and ethnical diversity- Burkina Faso counts about 60 different ethnicities- the community has built in security valves: the parenté de plaisanterie or the 'tease relationship'.]

"It's incredibly intriguing, and you sense that in the community which is pretty peaceful. For instance, the Senufo and the Peul have closed an age-old pact which preclude that they will ever have disputes. Both groups can swear at and mock each other, but it can never escalate to a conflict. Though there are quite a few codes that are unknown territory for me and which are more cruel. Stealing is a deadly sin. If you get caught, you're a dead man. When that happens, everyone goes outside to kill that person on the spot, so the only place thieves are safe is the police station. The flipside of this hard method is that stealing hardly ever happens."

[Burkina Faso is a religious country, in which the largest groups are followers of traditional religious practices like animism and the Islam. About twelve percent is Christian.]

"I kept myself a bit at a distance. I'm not religious and a person who is averse to religion isn't appreciated. Yet, we have some songs that have a strong link to religion, like Ala No Man Di, which is about the inscrutability of God. It is a beautiful song that Awa, who is a very religious Muslim, sings solo."

Awa Démé says:

"Allah is always close by. This isn't always an obvious choice for everyone. In Ala No Man Di, I talk about how difficult it can be to believe in God. God embraces everyone's lives: those of the suffering and those of the fortunate. There are some who have an un- lucky fate, they lose everything and everyone they cherish. And there are some who are predestined for luck, who have never had any problems. What they want, they get. Exactly those differences in destiny and the question why those differences exist, makes the challenge to believe in God even greater."

[Awa Démé was born into and grew up in the tradition of West African griots, and never learnt another language other than the spoken word.Like many young Burkinese she thought about one day leaving the hopelessness of her dried up, hungry country.]

"The people are tired of working, of fighting to get food on the table every day. It's an easy choice: leave, in search of a better life, food and drink elsewhere. Except, not everyone has that choice. And that's what Wait For Me is about."

[She sings about the desire to leave in the beautiful duet A Ni Baara, in which Carlens describes the hard reality of labor immigration. A reality that also exists in Burkina Faso: many Burkinese are forced to work for hunger wages in the cacao and banana industry on the Ivory Coast to feed their families.]

"I personally found a new opening with this project. This dialog with foreign countries has thrown open my world. This dialog works both ways", says Démé. She gives and learns. She learns new codes and new languages, both formally as concerning content, with which she wants to enrich her knowledge and personality. At the same time she adds the immense cultural heritage she carries within her to the European musician's baggage.

"A griot is a living library", says Démé. She calls herself a vessel filled with stories about the past, the present and the future. "It is my duty as a griot to tell these stories. That I can share these stories of the West African Mandingo culture across the border, that Stef is doing something with it, is a beautiful thing. Wait For Me has become a very open project, with musicians who really respect each other. We all support the result and you can feel that."

Ibrahim Diallo says:

"When I saw a Zita Swoon concert in Antwerp, it immediately became clear to me that I wanted to work on a project with Stef Kamil Carlens."

[Ibrahim Diallo is the artistic partner in Burkina Faso of world culture center Zuiderpershuis, whose support played a crucial part in the birth of this project.]

"Stef has an amazing talent to relate emotions, to bond with other cultures and traditions, to make connections. He's someone who purifies music and brings it back to its true essence. At the same time I thought it was an asset that his group- a nest of Flemish musicians, Cubans, Africans, Mestizos- is a 'multicoloured affair'.

In Wait For Me every musician takes in an equal position on an open horizontal plane. You feel that Stef is there, that the balafon player is there, the bassist, the griot. The whole thing works through mutual respect and coherence."

[The texts and dialogs hit on the morale and problems in the Burkinese community. Diallo took Carlens to his country and gave him an introduction to contemporary Burkina Faso, not just on a cultural level but also on a political and social level. Diallo, who has been affiliated to the Zuiderpershuis for seventeen years, founded the cultural center Le Grenier Culturel in the Burkinese city Fada N'Gourma. It has become a central meeting place between West Africa and Antwerp.]

"I dream of touring with Wait For Me through West Africa. Of course it isn't a political meeting, but you need to offer a dialog like this, so pure, the opportunity to flourish. It has become an honest and equal transaction between two cultures. You read the economic and political worries between the lines of the texts. You read what is wrong, what doesn't work. I love my country; it's a beautiful country with honest people. I don't have a desire to leave. Why should I? I believe it's possible: that everyone will be able to bring food on the table every day. It sounds banal, but food is crucial for happiness. You can only start being creative when you can eat and are healthy. You don't need to build a 3-story concrete building to know the richness of life."

[Spirituality runs parallel with the lines of life for Diallo:]

"Life is my guide and my inspiration. To be able to live a good life according to what the day brings, that is my goal."

From an interview by Tine Danckaers – Mo Magazine